Bob Stuart's MQA – Vision or Hype?

Bob Stuart is mainly known in the hi-fi scene as co-founder and developer of Meridian Audio. For several years now, however, the Brit has been making headlines with the audio codec MQA. With this new format, Stuart aims to revolutionize the music industry. With the recent launch of MQA streaming on Tidal in hi-res quality, he may already have succeeded.

A controversial topic

Since the first introduction of MQA (Master Quality Authenticated) in 2014, discussions have been flaring up around the world. And as usual, when something new emerges in the world of high-quality audio reproduction, these discussions are unfortunately often marked by prejudice, wild speculation, and ignorance. At least when it comes to ignorance, this is somewhat excusable in this context, because without profound knowledge of digital audio data and current developments in information theory, MQA is difficult to explain, let alone understand.

Why MQA?

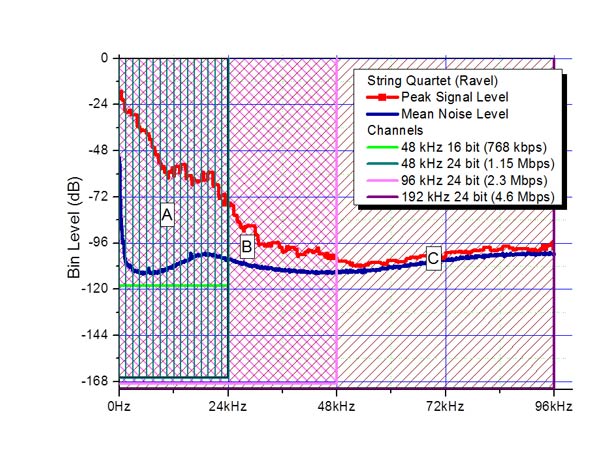

(Very) simply put, Stuart and his business partner Peter Craven see the current "hi-res" trend towards ever higher sampling rates and resolutions as a misdirection. It has long been a recognized fact that audio information beyond the previously postulated "threshold of hearing" at 20 kHz can have a definite impact on the sound quality of a recording. That's why digital recordings with more than CD quality (44.1 kHz/16 bit) do make sense (A digital music file can represent audio frequencies up to the so-called Nyquist frequency, which is half the sampling rate. So, a file with 44.1 kHz can reproduce frequencies up to 22.5 kHz.) According to Stuart and Craven, the actual information content that can be captured with higher sampling frequencies is comparatively low, but comes at the cost of a massive increase in data rate and therefore file size. In other words, a file with 96 kHz/24 bit is more than twice as large as the same piece in CD quality, but by far does not offer twice as much audio information. This effect becomes even clearer when going from 96 kHz/24 bit to 192 kHz/24 bit. Here, the file size again doubles, but the gain in information is only minimal. The vast majority of the additional data is (according to Stuart and Craven) wasted on digitizing silence and noise.

Origami with music

MQA takes a different approach here. The codec focuses on the area where most of the music information is found and preserves it perfectly. The additional information in higher frequency ranges is captured in compressed form and essentially hidden in the noise area of the lower frequencies. This process, which Stuart describes as "music origami," can also be repeated: The information of a 192 kHz / 24 bit recording is first "folded" into a file with 96 kHz / 24 bit, which is then again folded into 48 kHz / 24 bit. The resulting file can finally be saved as a FLAC container and is only slightly larger than a conventional FLAC in CD quality (MQA mentions about 20 - 30% additional file size), yet much smaller than a hi-res file. This file can now simply be streamed or downloaded and played back in CD quality on any conventional playback device. However, if the playback device is equipped with an MQA decoder, it can "unfold" the music origami it contains and play the recording in its original high-resolution master quality.

Video: Bob Stuart explains MQA's music origami (English)

Is MQA lossless?

So much for the (really strongly simplified) theory. However, this is where the first heated discussions began immediately after the announcement of MQA, for example, about the question of to what extent MQA can really be regarded as "lossless." And Bob Stuart has since then expressed himself very eloquently to avoid answering this question directly. While it still seems understandable that much of the information contained in the upper frequency range can be stored in a data-reduced manner without actual loss of information, the question remains as to how and where this information is hidden in the resulting file. At least with regard to the pure digital data, information must be lost somewhere. Therefore, at Wikipedia, MQA is also described as "lossy." However, Stuart insists that no musical information is lost, only uselessly digitized noise, which, moreover, could be restored during file decoding through appropriate filtering.

MQA always sounds better!

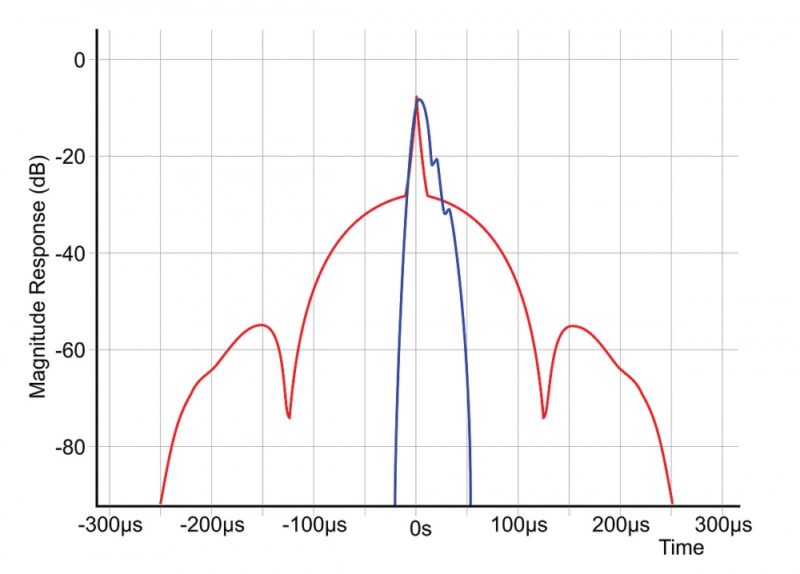

MQA, Bob Stuart, and increasingly others even go one step further: An MQA-encoded piece of music is said to sound better even when played on a device that is not MQA-capable. That sounds surprising, but it actually isn’t far-fetched, because this is where the "authentication" in the name Master Quality Authenticated comes into play. MQA does not see itself as a mere codec, but rather as a standard that encompasses all aspects of digital music distribution, from recording to playback. The vast majority of the digital music catalog available for streaming or download was created by digitizing original analog master tapes. Especially with older digitizations, but to some extent even today, the analog-to-digital converters used in this process generate varying degrees of sampling inaccuracies. To put it very simply: Up to the already mentioned Nyquist frequency, digital sampling can actually perfectly reproduce the different frequencies of a music signal. However, representing the slopes of the signal, i.e., the attack and decay of the tone, correctly is considerably more difficult, especially for high tones whose frequency is close to the Nyquist frequency. The filtering used in A/D conversion creates a "slower" signal here, that is, a signal with lower slope steepness. In addition, both the attack and decay sides produce artifacts, so-called overshoots (ringing). Especially overshoots on the attack side can drastically affect the subjectively perceived sound quality, since they never occur in naturally occurring sounds. Stuart and Craven summarize these effects under the term "time smear." In their view, every digital file based on a tape master is inevitably affected by this. However, the two tinkerers have recognized that these errors have a very typical signature for every A/D converter used, like a kind of fingerprint, and therefore can be corrected.

Philosophy and business

Bob Stuart is often quoted as saying that MQA is much more a philosophy than a codec. And certainly, no one wants to deny the experienced tinkerer his love for music and its optimal reproduction. But it is also a fact that Stuart, Craven, and their company MQA, Ltd. want to make money with this technology. To fully enjoy MQA sound quality, you need at least an MQA-certified D/A converter. And, of course, manufacturers of MQA products are supposed to pay a license fee for each device sold, as are music studios and streaming services that want to promote their offerings with improved sound quality. That probably also explains why prominent representatives of hi-fi manufacturers are loudly joining the MQA discussion on the internet and elsewhere. Apart from the license costs that integrating MQA into their devices would entail, many fear interference in the construction of these devices. MQA mandates the use of certain chipsets for decoding and authenticating MQA. What exactly happens in these chips is, of course, only known to MQA; all other manufacturers, as far as is currently known, would have no influence on this. In particular, companies like PS Audio or Chord Electronics, which have so far relied on self-developed D/A converter algorithms based on freely programmable FPGA chips, would have to completely change their technical approach if MQA were to become an indispensable standard in the hi-fi world.

Playing MQA

Probably also for this reason, the list of partner manufacturers at MQA is still rather manageable. But alongside - unsurprisingly - Meridian, there are already some big names like Pioneer, Onkyo, Technics, and NAD, as well as smaller specialists like Mytek, Aurender, or Brinkmann. The name Bluesound also appears on this list, and due to recent developments, this multiroom offshoot of NAD occupies a special position in the market. Until recently, as is usual with the introduction of a new standard, the very limited amount of available MQA music was one of the main arguments of critics. There has been a framework agreement with Warner Music for some time, and on download platforms like HighResAudio.com or Onkyo Music, corresponding music is available for purchase. But in the grand scheme of the music industry, a few hundred audiophile albums are little more than footnotes. But since the beginning of January, the MQA world looks very different.

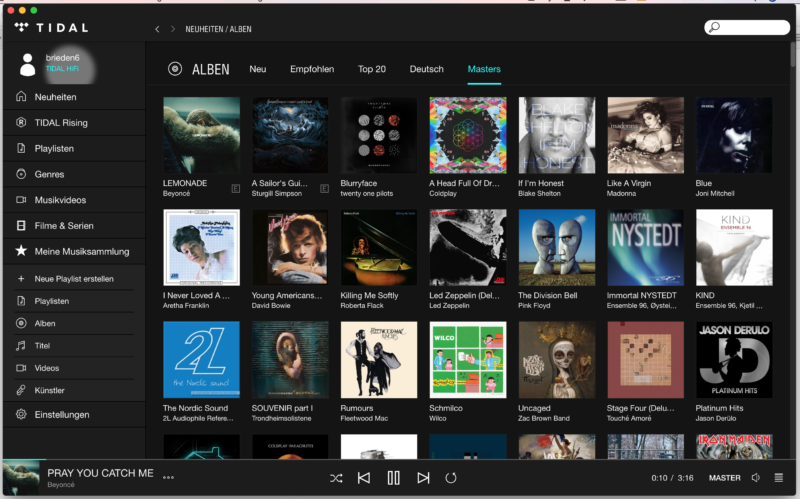

MQA and Tidal

Right on time for the start of CES, the long-announced collaboration between MQA and the streaming service Tidal was finally launched. All subscribers to Tidal's premium offering, called "HiFi," can now stream selected albums in original master quality. Even though the selection is still limited, at least numerous classics of pop and rock history as well as recent material from popular artists such as Beyoncé or Coldplay are already available for streaming at any time. There is little doubt that streaming represents the future of the music industry as a whole. But for true hi-fi fans seeking the best possible sound quality, high-resolution downloads have still been the method of choice in the digital realm. But if MQA also delivers the promised quality in streaming and Tidal fulfills its promise to offer all new albums in MQA from now on, there is now at least an interesting alternative.

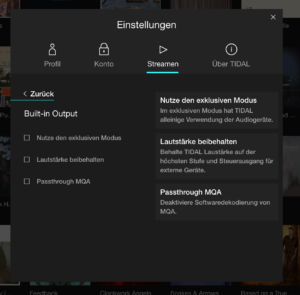

MQA with Bluesound

There is still one small limitation at present, and this is where Bluesound comes back into play. Currently, Tidal's MQA support is limited to the desktop versions of the Tidal software for Windows and Mac. Mobile playback devices and other systems are initially left out. All other systems? Not quite, because one plucky British-Canadian manufacturer of high-quality multiroom systems has done its homework and was able to offer a playback option at the launch of MQA on Tidal that does not rely on a computer. All Bluesound products, including the control apps for iOS and Android, can already play MQA streams from Tidal in full master tape quality. This includes, for example, the Bluesound Node 2, which is simply connected to the existing hi-fi system and thus makes any system MQA-capable.