Perspectives - What is beautiful?

Text: Olaf Adam; Photos: Shutterstock, Wikimedia Commons

This article originally appeared in 0dB - Das Magazin der Leidenschaft N°3

Rock 'n' roll or Beethoven? Picasso or Hopper? A cozy Sunday on the sofa or an alpine hike? We all find different things beautiful. But is there such a thing as "true beauty"?

First of all: On the following pages, you will certainly not find a definitive answer to the question posed in the introduction. The greatest minds in world history have already puzzled over the nature of beauty without coming to a universally valid answer.

Thoughts on Beauty

Plato, for example, assumed that true beauty, "beauty itself," actually exists—as a kind of archetype of beauty, a pure, perfect, and immutable metaphysical reality. According to his view, this escapes human perception, but it can be grasped intellectually. Things that humans can perceive with their senses possess, at most, a relative beauty—they are only beautiful in part or from a certain perspective, they can be overshadowed by something more beautiful, or lose their beauty altogether.

More than 2000 years later, Goethe agreed with the Greek thinker: "Beauty is a manifestation of secret laws of nature, which would have remained forever hidden from us without its appearance." So is it really the case that there is a "true beauty" that we humans sometimes recognize more, sometimes less? It doesn't seem to be that simple. At least Goethe's contemporary Schiller located the perception of beauty not necessarily in reason: "Truth exists for the wise, beauty only for a feeling heart."

Beautiful People

If you type "beauty" into an internet search engine today, most of the results are cosmetic tips and women's faces. Obviously, at some point our society decided to primarily relate the term to the appearance of people. There must be reasons for this—so maybe answers to the question "What is beautiful?" can be found there. To begin with, beauty in this context is inevitably a construct, shaped by the time, the culture, and individual circumstances.

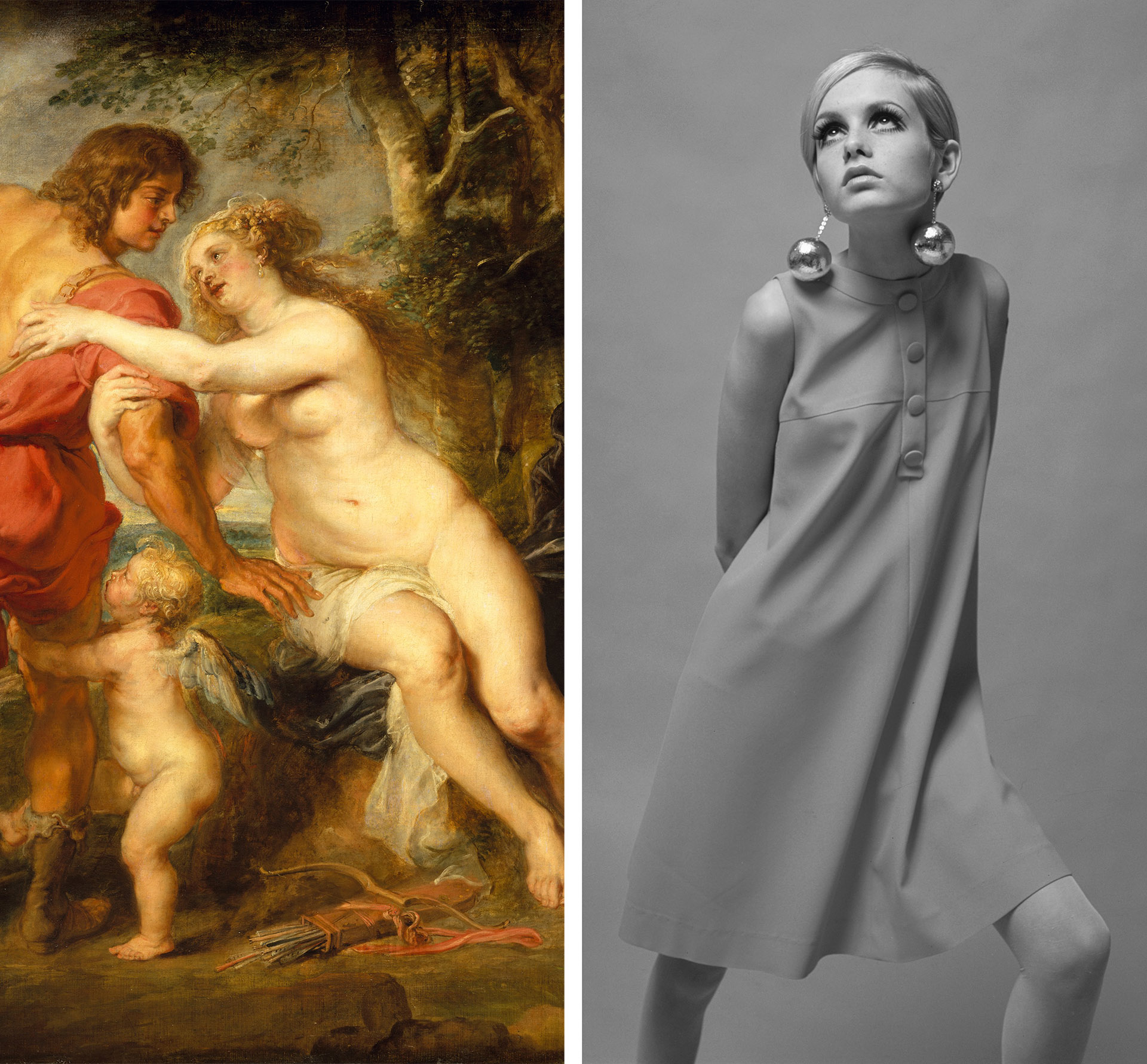

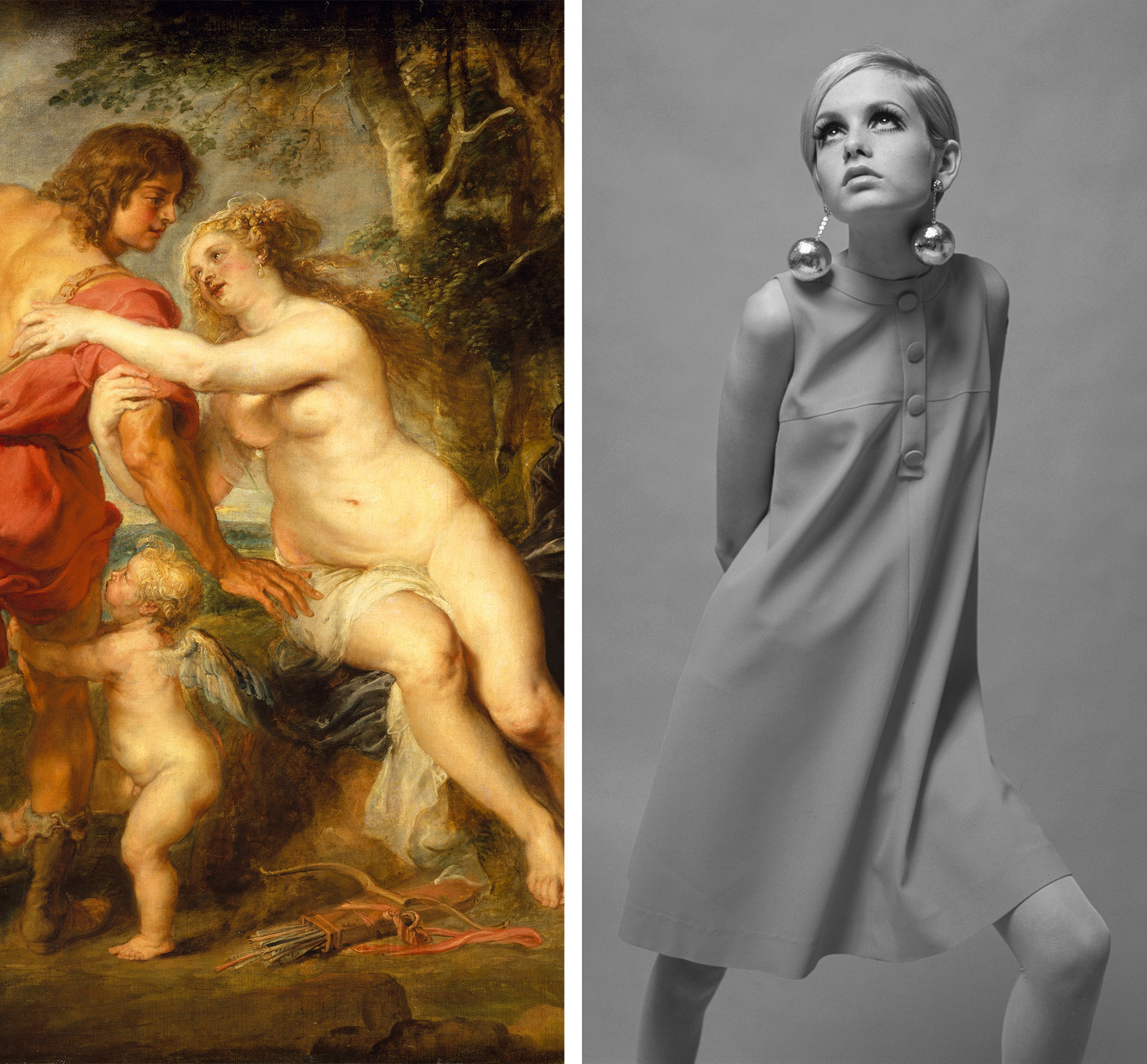

Just consider the so-called ideals of beauty throughout history. There is a world of difference between Rubens' well-proportioned female bodies in the 16th century and the Twiggy fashion of the swinging sixties in the last century. But do such ideals have anything to do with true beauty? Hardly. They are more a notion created by a society and spread by the media of the time about how people ought to look.

And since the world is as it is, these "ideals of beauty" over time have been almost exclusively applied to women. Or should one say, they have been used against them? Considering the many illnesses, impairments, and mutilations women in various cultures have suffered and continue to suffer today in order to conform to a certain "beauty" ideal, this interpretation almost suggests itself. Men, on the other hand, could almost always and everywhere look as they wished, as long as they could squeeze themselves into the latest fashions.

Such comparisons are, therefore, almost certainly unsuitable for the search for true beauty. And yet, it is undeniable that we find some people beautiful and others less so. This applies especially to faces, and here, symmetry seems to play an important role, quite independently of cultural influences.

Beautiful or Attractive?

Science usually assumes that we find people attractive who appear healthy, and that is why a symmetrical face, even skin, and other signs of physical health are perceived as beautiful.

From an evolutionary biology perspective, there may be some truth to this, but this explanation is not entirely convincing. Studies with artificially generated portraits have shown that a face can also be too perfect. If a computer creates the mathematically ideal face, the result apparently lacks the necessary dose of reality—a small, endearing deviation from the ideal that turns a beautiful image into an attractive person. When it comes to human relationships, we need to distinguish between beauty and attractiveness. The latter is too heavily influenced by our culture, our preferences, and our hormones to allow a reliable statement about the former.

Perfect Proportions

So let us, for a moment, withdraw from the mix of human feelings, cultural phenomena, and biological processes and look for evidence of the existence of true beauty in more tangible areas. And indeed, there appear to be some mathematical principles of beauty, whose deeper meaning is still not fully understood.

The most well-known example is probably the golden ratio. The term was coined in the mid-19th century, but the mathematical principles were already known to Euclid (around 300 BC). The golden ratio occurs when a line (or other quantity) is divided so that the ratio of the whole to the larger part is the same as the ratio of the larger part to the smaller. This ratio, the golden number, is an irrational number with infinitely many decimal places, but is approximately 1.62, or a division of about 61.8% to 38.2%. For non-mathematicians, this all sounds very abstract at first, but we encounter the golden ratio and the golden number daily without realizing it.

It has been proven that we perceive proportions that follow this principle as particularly harmonious and beautiful. And that is why, for centuries, it has been applied in art, architecture, and the design of everyday objects. One could, of course, also suspect a cultural influence here and assume that over time we have "learned" to find such proportions beautiful.

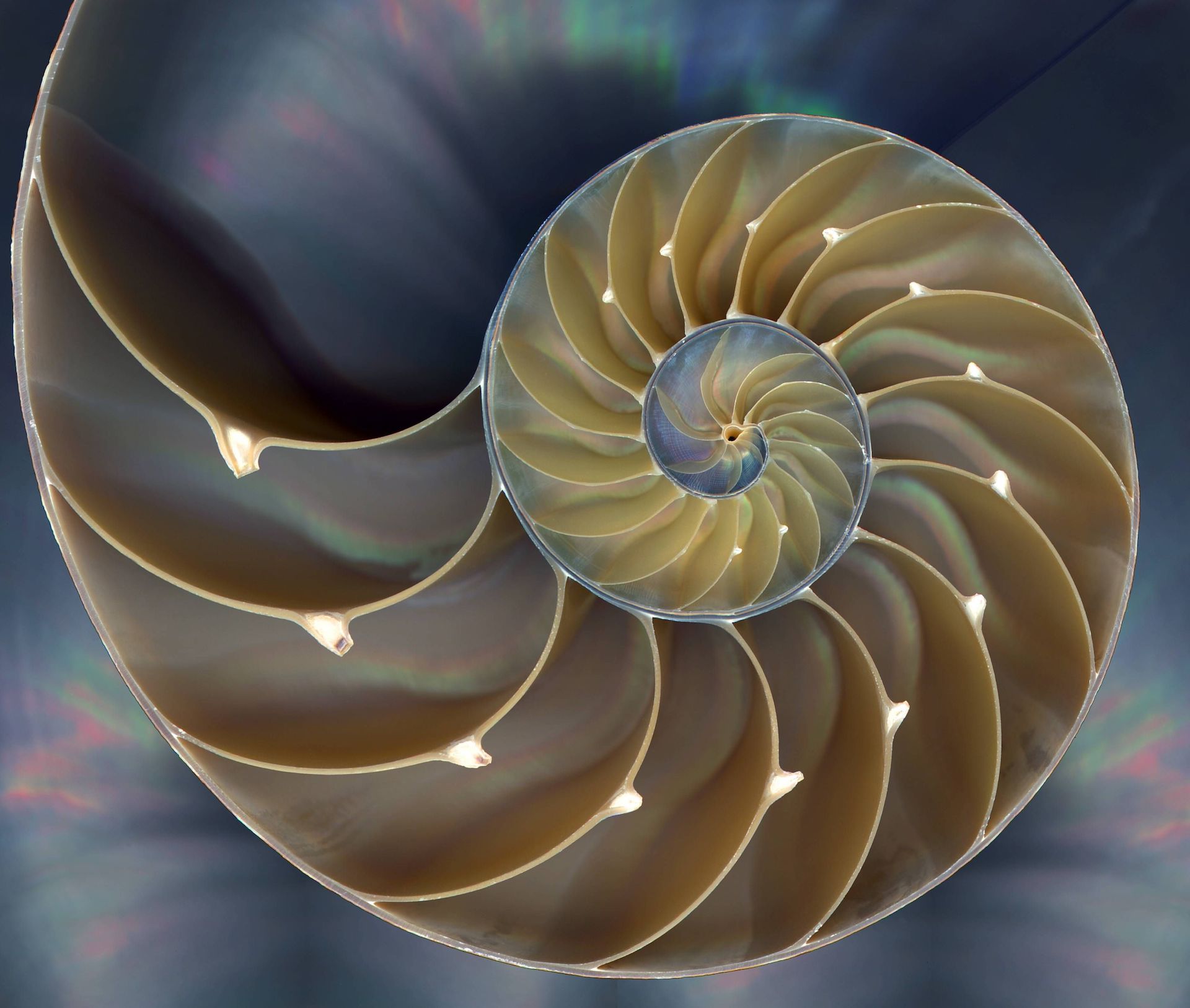

The Blueprint of Nature

But in fact, there seems to be more to it, because, surprisingly, the golden ratio can also be found in nature. The arrangement of leaves around the central axis of many plants follows this ratio, pine cones, the flower heads of sunflowers, and seashells are arranged in so-called Fibonacci spirals, which are mathematically based on the golden ratio. The golden number has also been identified as a decisive parameter in crystal structures, the resonances of planetary orbits, and even certain aspects of black holes.

So can beauty be reduced to this single number, does it follow a kind of cosmic law? Unfortunately not, or at least not exclusively. There are numerous examples in nature and art that are beautiful without the influence of the golden ratio. Not all plants follow its rules, and in music, if anything, other mathematical aspects are relevant.

More Than Numbers

In the visual arts, classical beauty is often understood today as a kind of superficial embellishment, while "real" art is meant to provoke emotion, inspire thought, or comment on society. Beauty is secondary, perhaps even an obstacle, and works created with this in mind often strike many people as downright ugly. Others, however, find them beautiful and enjoy looking at them. Many aspects of beauty are, in any case, beyond the grasp of mathematics and theory. How can you quantify the breathtaking beauty of an alpine panorama, or the moment when your own child takes its first steps? Can you measure how beautiful a tender touch is, or does the objective beauty of a sunset really increase when you share it with someone you love?

Hardly, since every theory of beauty has little, and often nothing at all, to do with real life. No matter what psychology, mathematics, social science, or aesthetics say, in the end the rule is: Beautiful is what pleases.