Sphärenmusik - Art and Math

Text: Andreas Günther; Photos: Photocase, Shutterstock

This article originally appeared in 0dB - Das Magazin der Leidenschaft N°3

Why does minor make us sad, and why do we rejoice in major? Because an ancient Greek once eavesdropped on the planets as they traveled along their paths. Bach and the Beatles followed his mathematical rules.

Pythagoras. That name still sends shivers down the spines of many math students today. The great Greek philosopher not only laid the foundations of modern mathematics, but he is also the creator of our musical culture. Pythagoras lived around 500 BC, spent some years in Egypt, and studied the local number mysticism. In his view, humans are ruled by gods, numbers, and proportions. The highest form of spiritual approach to the gods for mortals – is through music. Music that encompasses the entire universe.

A wonderful idea: the planets circle through space and produce tones as they do so. Inaudible to humans, purest music of the gods – but able to be translated by and for mortals. Two terms from this philosophy have made it into our modern language: the individual tones of the "music of the spheres" create a magical harmony, the "Symphonia." The worldview of the ancient Greeks also had misleading aspects from today's perspective. One can still understand that the school of Pythagoras believed fast-moving planets made loud noises and that pitch was determined by proximity or distance to the center of the universe. But the idea that the center of the universe was the tiny planet Earth is something that only makes us smile today. Yet this doesn't diminish the fascination with the music of the spheres.

Resonant celestial bodies

Even the enlightened, knowledgeable Goethe clung to this poetic idea 2000 years later. He opens his famous "Faust" with a "Prologue in Heaven," letting the archangel Raphael proclaim: "The sun sounds in ancient manner / in brother spheres’ competition of song, / and completes its prescribed journey / with thunderous stride." Pythagoras tried to do the impossible: to capture the sun in tones, a translation of the sound of the stars into resonant mathematics. For this, he built himself the instrument of all instruments: a "monochord." This "instrument" with a single string was used according to mathematical specifications. Or rather, divided. The system of Pythagoras still works today. If you divide a string exactly in half, you get the octave of the fundamental tone. That is, a vibration ratio of 1:2. Pythagoras divided the string into a total of twelve units – which represent our modern chromatic scale of twelve half-tones. Eight defined tones played in succession form a scale. Three defined tones struck at the same time form a triad, which determines harmony. The characteristic feature in this triad for our ears is the middle tone: the third. A "major third" is defined as bright, broad, and open – the major mode. A "minor third," on the other hand, sounds sad and dramatic to us – the minor mode. Even the etymology reveals the emotional meaning: major comes from the Latin "durus," "hard" – minor, on the other hand, from "mollis," "soft."

Warning: wild delight!

Terms their inventor Pythagoras would not have understood. Western musical reality has simply abolished a number of other modes over the centuries. Today, hardly anyone plays "Lydian," "Phrygian," or "Dorian." In a critical sense, our tonal system has become impoverished – the two poles of major and minor define a world that was already richer, but also darker, in Plato's time. For Plato, music was not just beautiful but also dangerous. The philosopher called for state supervision. Since music could inspire "wild delight," democracy had to be protected against intoxicated uprisings. Moralists raised the same outcry years later at Berlioz, Wagner, Elvis, and the Beatles.

The "Phrygian mode" was especially despised by the noble Greeks. Here, orgiastic music raged with flute, clapper, and hand drum – especially among the lower social classes. The pop music of antiquity. If Plato had had his way, educated Greeks would have been allowed to hear only the Dorian mode. This mode made people "stronger against fate," could create inner balance, and was considered knightly and manly. The Lydian mode, on the other hand, was considered more feminine: the mode of the delicate and intimate. Aristotle demanded it as the standard for the education of youth. In his "Politeia," Plato objects: "... we cannot use lamentations and wailing, so the Lydian modes must be eliminated; for they are useless for women who are supposed to be brave, let alone for men." Likewise, the "soft and suitable for drinking parties" modes – including the Ionian sub-mode – were considered despicable. In retrospect, a difficult-to-understand philosophy – after all, the Lydian is closest to the modern major, which for us proclaims energy, strength, and joy.

Listening is cultural enslavement. We are over 2000 years removed from the diversity of ancient modes. Modern humans are conditioned to major and minor, at least in the Western cultural sphere. We are at home in this system, but also trapped by it. The poverty is self-inflicted. Even in the Middle Ages, monks sang in up to eight different modes plus sub-modes. God was praised in Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Ionian, Aeolian, and Locrian. Some modes have survived in the niche of Protestant and ecumenical hymnals. Bach (1685–1750) still knew how to compose in Dorian, and even Beethoven (1770–1827) was tempted to write a string quartet in Lydian mode (Opus 132, 3rd movement, F major with b natural instead of b flat).

New and foreign systems evoke rejection, and not infrequently, fear. In the 20th century, Arnold Schönberg (1874–1951) wanted to free concertgoers from the captivity of major and minor and lead them into the promised land of the twelve-tone system. The success of "dodecaphony" has been limited to this day. The revolution of some instrument makers who built pianos with quarter-tone intervals ended even more sadly – slow sellers in music history. Pythagoras remains the shaper, but also the dictator, of our listening experience.

Pythagoras must stay after school

Only in one respect does the teaching of Pythagoras fall short. Every student who has suffered through the "Pythagorean Theorem" should once ask their teacher about the "Pythagorean comma." Few teachers will be able to explain the phenomenon without stumbling. The problem is fascinatingly beautiful: the music of Pythagoras is the mirror image of the solar system – they confirm each other. The perfection of the theory holds even in its smallest irregularity. For example, the year can only be divided into 365 days with difficulty – every four years, a leap day must be added to February.

Fascinating equation in the music system: here, too, corrections are made – if you build up twelve Pythagorean fifths and compare them to the tone that, mathematically, seven octaves should reach, you find a difference – the "Pythagorean comma." For the mathematically meticulous among us: seven octaves correspond to a frequency ratio of 1:128 – twelve fifths, on the other hand, to a ratio of 1:129.746337890625. A tiny difference, but one that drove subsequent generations of musicians to the edge of compositional freedom. Especially with fixed-tuned keyboard instruments, harmonic fantasies had to be avoided; the tiny difference could accumulate into harsh dissonances in distant keys. For this reason, 2200 years after Pythagoras, various musicians tinkered with a new form of scale. Also a numbers game. Andreas Werckmeister distributed the slight irregularities of the Pythagorean comma across all the semitones around 1700 – "equal temperament" was born. A small step for an instrument maker, a giant leap for music history – since Werckmeister, no instrument has sounded "purely" Pythagorean. The famous "Das Wohltemperirte Clavier" by Johann Sebastian Bach is a direct response to the new possibilities – a universe of preludes and fugues that ventures into distant keys. In a way, the Starship Enterprise of all piano literature.

Other countries, ...

Most people follow the rules of major and minor? Not at all: the Chinese people, for example, can make little sense of "our" music. In the Middle Kingdom, music is governed by the rules of the "pentatonic" scale. Instead of seven notes, the tonal "alphabet" in East Asia only knows five. In Arabic music, the octave is divided into 24 equal intervals. The three-quarter tone is identified by musicologists as a key characteristic. Hard for Western ears to grasp. Classical Indian music impresses with the aura of the small and subtle. At its core, only one instrument is allowed to play the melodic line. Another harmony instrument is tasked with drone tones – unchanging sustained notes. To this are added one or two percussionists with rhythm instruments. The tonal range within an octave includes 66 microtonal gradations, though in practice, 22 steps are used.

Again: listening is cultural enslavement. In Western culture, we owe the basis to the intellectual work of Pythagoras. A fascinating idea: Beethoven, Bach, the Beatles, and James Last all composed according to the same rules formulated by a Greek philosopher as he hammered away on a wooden box with a dried goat gut.

Listening tips

The classical boundary breakers

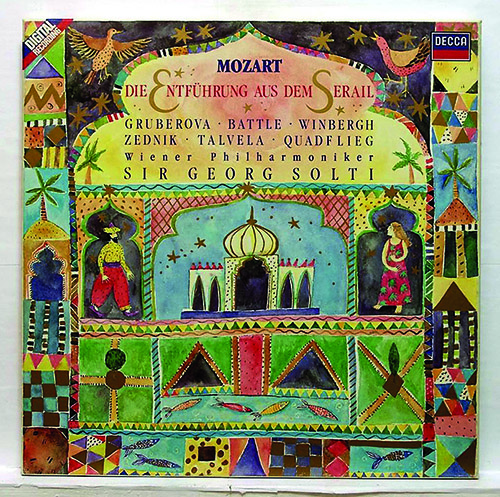

Mozart – Die Entführung aus dem Serail

This opera was not only stylish in Vienna in 1782, but downright revolutionary. Mozart takes the audience into a harem(!) and explores the musical language of the Turks – including a chorus of "Janissaries," the elite soldiers of the Turkish empire.

Top recording:

Edita Gruberova, Gösta Winbergh – Sir Georg Solti (Decca)

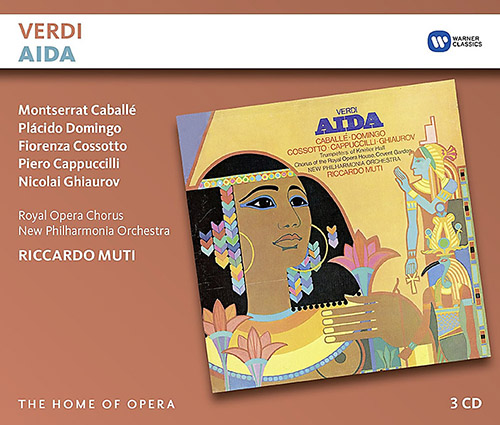

Verdi – Aida

Giuseppe Verdi seriously explored: what did music sound like in ancient Egypt? He found wonderfully shimmering, exotically beautiful tones. His most famous idea is used – and misused – at every soccer match today: the triumphal march played on a specially developed

fanfares trumpet – incidentally designed by Adolphe Sax, the inventor of the saxophone.

Top recording:

Montserrat Caballé, Placido Domingo – Riccardo Muti (EMI)

Mahler – Das Lied von der Erde

Music between ecstasy and sorrow – with strong echoes of what Western ears associate with "Chinese." Gustav Mahler set six poems by ancient Chinese poets to music. Grand symphonic writing, highly emotional, fascinatingly orchestrated, and a real treat on good speakers.

Top recording:

Fritz Wunderlich, Christa Ludwig – Otto Klemperer (EMI)