Streaming: Who’s Really Exploiting Whom Here ...?

by Olaf Adam

It started with Napster and Deezer, became increasingly popular through Spotify, and the spectacular launches of Tidal and Apple Music finally dragged the topic into the mainstream spotlight: music streaming is a huge thing, and for many, it’s nothing less than the future of music distribution. But at the same time, there’s a lot of noise. Many musicians complain about the low revenues from streaming and quote amounts in the hundredth-of-a-cent range per stream. Fueled by the fast-paced subculture of social media, this accusation has been repeated thousands of times and is now considered a fact by many. People talk about the exploitation of artists, even about modern digital slavery. The culprits are—logically—the stingy streaming services and their customers, who support this outrage millions of times over. Question it? Unnecessary. Do a bit of research yourself? Much too exhausting! Yet, it would actually be relatively simple to break down this train of thought in just a few steps. And that’s exactly what the Berklee Institute of Creative Entrepreneurship has recently done in the study Rethink Music. So let’s start at the beginning:

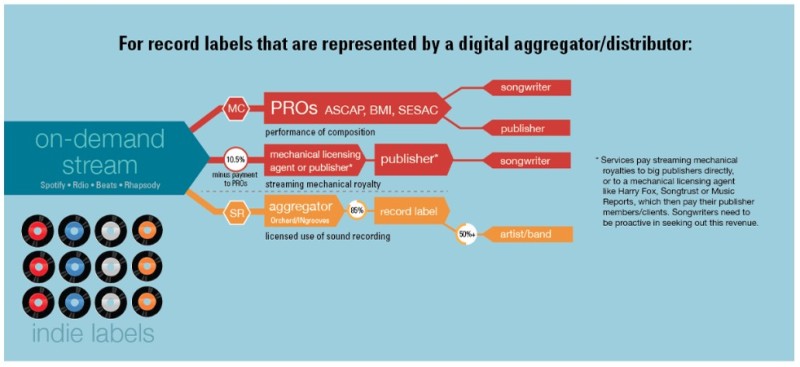

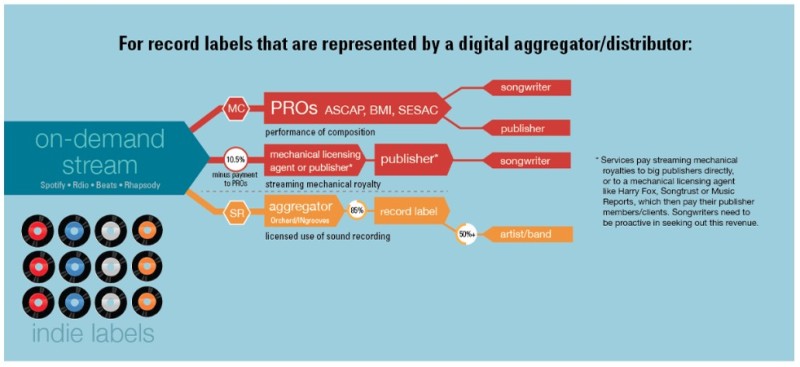

With whom have the streaming services made their contracts, and to whom do they consequently pay money?

To the artists? Yes, if their name is Madonna, Jay-Z, or Beyoncé and they own extensive rights to their own songs. But for 99% of musicians worldwide, that’s not the case. They have assigned their exploitation rights to their labels, meaning the music companies. In return, they’ve signed contracts that specify exactly what share of the revenue they receive themselves. So the streaming services have nothing to do with this; they simply pay their distributions to the labels.

Are the streaming services enriching themselves at the expense of the artists?

Uh... no. Of course, these companies want to make money from streaming, and that’s their good right. To do this, they keep a certain share of revenue from ads and subscriptions; the rest is distributed depending on the number of plays. This share, about 30%, is by no means outrageous, as it’s pretty much exactly what, for example, is kept from an iTunes sale. And the streaming providers themselves would probably confirm that this share is rather low, since apparently none of them has ever been profitable so far, with all revenue currently being invested in marketing and technical infrastructure. So, about 70% of streaming revenue goes to the rights holders. And in most cases, those are the labels.

Is streaming just too cheap and devalues the musical work of artists?

That’s certainly, to some extent, a question of market self-regulation, and also a matter of opinion. It’s true that there have always been some people willing to spend a lot of money on music. But there have always been far more people who simply weren’t willing to do so. And this trend reached its sad peak at the end of the nineties and the beginning of the 2000s, when millions of illegally shared MP3s actually caused severe damage to the music market and plunged the industry into a deep crisis. But it’s also important not to forget that, for several years now, global music revenues have been rising again. And that’s largely thanks to the growing streaming business. One also has to be realistic when looking at this situation. For a dedicated hi-fi fan, it’s certainly nothing special to spend 30, 40, or more euros a month on music. And nothing is stopping them from continuing to do that. But among the general population, this willingness has not existed for a long time. Only streaming services have managed to reverse this trend. On average, a subscriber to Tidal, Spotify, and the like pays about 120 euros per year. Every year. That’s a lot of money and certainly more than many customers spent on music just a few years ago. The rising revenues of the music industry prove this positive development.

Are artists simply getting too little money per stream?

Unfortunately, that’s true. But the ones to blame are not the evil streaming services, but the labels. And, to some extent—this has to be said—the artists themselves; after all, they signed their contracts. However, the behavior of many (all?) labels borders on outrageous. Artists receive only their contractually agreed share of direct streaming revenues. But the labels profit on other levels from streaming as well. For example, there is often a kind of base fee that streaming providers pay to the labels just to make their catalog available. It’s unclear whether, and how, individual artists benefit from this revenue. Some labels have also secured company shares in various streaming services and, in return, agreed to receive reduced payouts per played track. What this means, in plain terms, is that in these cases the labels are earning double, but only have to share a much smaller part of that with the artist.

So, who is exploiting whom?

Well, dear Taylor Swift, dear parroters and finger-pointers. Not everything in life is so simple that it fits into a 140-character tweet. And simple answers to complex issues are often dangerous. But if you absolutely want to try to summarize this topic, it can only be put this way: it’s not the streaming services exploiting the artists, but the labels. (Our thanks go to John Darko from digitalaudioreview.net, who brought the above-mentioned study to our attention.)